Gamebirds such as pheasants and red-legged partridges may not be species that to come to mind when considering intensively farmed animals, yet in the UK alone, around 47 million pheasants and 10 million partridges are released on shooting estates annually (1), most having been bred and/or reared in intensive conditions yet without the same legal protections as other farmed species.

Significant welfare concerns which can arise at all stages of breeding, rearing, transport, release and slaughter are briefly outlined below, in addition to some of the attendant welfare impacts on other species.

Transitory legal statuses...

Legislation to protect the welfare of farmed animals does not apply to gamebirds due to an exemption for ‘animals intended for use in ... sport’ (2). Whilst confined for breeding, rearing and over-wintering, and therefore considered ‘under the control of man’ the Animal Welfare Act (2006) instead applies, under which gamebirds should be protected from ‘unnecessary suffering’ (3). After release on shooting estates they are considered wild, yet have been exempt from the licensing usually required for releasing non-native species.

Breeding and Rearing Conditions

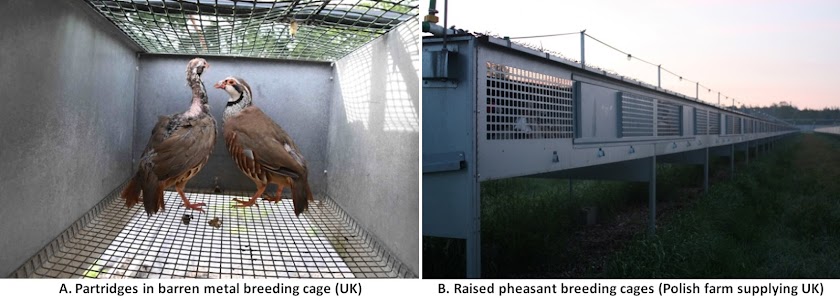

As with other farmed species, breeding and rearing conditions have become increasingly intensified. Cage systems used for breeding gamebirds such as barren raised cages for pheasants (typically one cock bird housed with several hens), and small barren cages for partridges (housed in pairs) have come under particular scrutiny due to welfare concerns associated with the cramped, barren conditions. DEFRA advises that these cage types should not be used (4), however their gamebird rearing code comprises guidance rather than stipulating legal requirements. Whilst some UK breeding farms use more extensive pen systems, others still reportedly use these barren cages.

Approximately half of the pheasants and 90% of partridges ultimately released on UK shooting estates, are imported (as hatching eggs or day-old chicks), from breeding farms in mainland Europe (where DEFRA’s code does not apply), the vast majority having originated from intensive farms (5).

On rearing farms, some operations use commercial poultry housing systems, however there are no minimum space requirements, and stocking densities may accordingly be very high. Others are reared in more traditional extensive systems on shooting estates (5).

The transport of young gamebirds to UK rearing farms or shooting estates can compromise welfare (5) due to potential stressors including long travel times, crowded or unsuitable conditions in crates, poor ventilation or limited protection from the elements with associated difficulties in thermoregulation.

Behaviour Management Devices

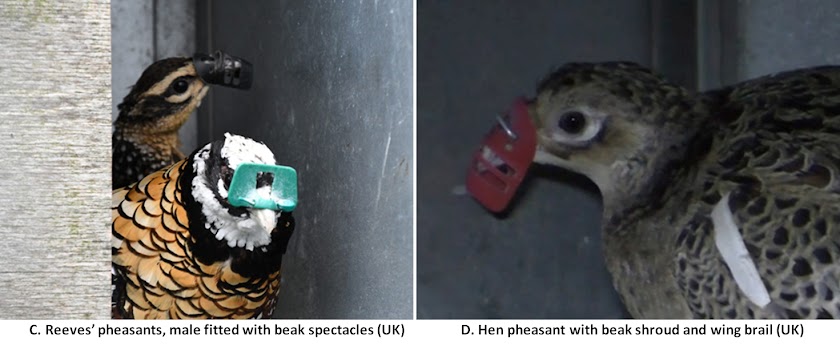

In confined conditions, feather pecking and inter-bird aggression can occur. These issues may be reduced by providing environmental enrichment, however this is not mandatory and management devices (bits, beak shrouds and spectacles) are also used. Brailles (which restrict wing movement) may be used with pheasants to prevent escape from open pens. The use of the above devices restricts normal behaviour and DEFRA therefore advises that their use should not be routine, instead emphasising better management practices (4).

There has been little genetic selection of the gamebird strains used and they have consequently retained many of their wild traits (5); as captive, essentially wild birds, they are potentially even less suited to confined conditions or handling than domesticated farmed species.

The Killing Fields

As many as 30% of gamebirds released are killed prior to the start of the shooting season by traffic, exposure to the elements, predation or starvation (5).

Gamebird killing on shoots is not covered under UK ‘humane slaughter’ laws. Again, exemptions apply for hunting or sporting events (6). Nor are participants required to have a proven level of shooting competence; up to 40% of birds may be wounded rather than killed outright (7). Invariably, not all wounded birds will be found, and may suffer for a considerable time until conditions are sufficiently safe for their retrieval (and dispatch). Despite the commonly held perception, most of the gamebirds killed at a shoot are not eaten, but simply discarded (7).

The wide-ranging welfare impacts on other species

Releases into the countryside of such a large number of non-native species have significant ecological impacts affecting the welfare of native species. (From 2021, some licensing requirements (8) may eventually be introduced.) Pheasants in particular kill large numbers of reptiles including the UK’s only venomous snake, the adder (which is on the brink of extinction in many areas). Gamebirds also compete with native birds for food resources, and can cause damage to habitats (7).

‘Predator control’ in order to protect gamebirds takes the lives of significant numbers of animals. Foxes and corvids may be trapped using methods including free-running snares and Larsen traps respectively, which have received strong criticism as inhumane, leading to bans in many other European countries (7). Weasels and stoats are also ‘controlled,’ and incidents of illegal persecution of birds of prey (geographically linked to shooting estates) have been widely reported. Furthermore, the lead shot used poisons the environment as well as animals who ingest it (7).

The ethics of shooting for 'sport' are outwith the scope of this blog post, however the significant welfare concerns at all stages of gamebirds' lives, in addition to the attendant impacts on other species and the environment clearly raise important questions regarding how this pursuit can reasonably continue to be justified.

References

1. Aebischer, N. J. (2019) Fifty-year trends in UK hunting bags of birds and mammals, and calibrated estimation of national bag size, using GWCT’s National Gamebag Census. European Journal of Wildlife Research, 65, (4), 64.

2. Welfare of Farmed Animals (England) Regulations 2007, No. 2078. Available at https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2007/2078/contents/made [Accessed 2 Nov 2020].

3. Animal Welfare Act 2006, Chapter 45. Available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2006/45/contents [Accessed 1 Nov 2020].

4. Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (2009) Code of practice for the welfare of gamebirds reared for sporting purposes, Ref: PB13356. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/code-of-practice-for-the-welfare-of-gamebirds-reared-for-sporting-purposes [Accessed 2 Nov 2020].

5. Farm Animal Welfare Council (now Animal Welfare Committee) (2008) Opinion on the Welfare of Farmed Gamebirds. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/fawc-opinion-on-the-welfare-of-farmed-gamebirds [Accessed 1 Nov 2020].

6. The Welfare of Animals at the time of Killing (England) Regulations 2015, No. 1782. Available at https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2015/1782/contents/made [Accessed 1 Nov 2020].

7. League Against Cruel Sports (2016) The Case Against Bird Shooting. Available at https://www.league.org.uk/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=39f5329e-40f8-4a86-97b5-1e8cd987c952 [Accessed 1 Nov 2020].

Photo credits (and further information)

A. Animal Aid (2017) Heart of England partridges with feather loss. Available at https://www.animalaid.org.uk/the-issues/our-campaigns/shooting/take-action-game-birds/ [Accessed 1 Nov 2020].

B. Hunt Saboteurs Association (2019) Klon2. Available at https://www.huntsabs.org.uk/polish-pheasant-imports-rise-by-2400-in-just-four-years/ [Accessed 1 Nov 2020].

C. Animal Aid (2017) Heart of England Reeves’ pheasant wearing beak spectacles. Available at https://www.animalaid.org.uk/the-issues/our-campaigns/shooting/take-action-game-birds/ [Accessed 1 Nov 2020].

D. Hunt Saboteurs Association (n.d.) Horrific Cruelty Revealed at Lancashire Pheasant Farm. Available at https://www.huntsabs.org.uk/horrific-cruelty-uncovered-at-lancashire-pheasant-farm/ [Accessed 1 Nov 2020].